I’m 70 years old. Every morning, I pack an old, second-hand cart with my wooden easel, a couple of blank canvases, and a set of oil paints I’ve been stretching thin for the past two months. Then I walk—slowly, carefully—five blocks to the park where I paint.

It’s the same spot I’ve been at since everything changed. I set up near the pond, by a crooked bench with peeling green paint. Ducks gather there, kids toss breadcrumbs, and their parents stare at their phones. This is where I work now. This is where I live, in a way.

I wasn’t always a painter. I spent 30 years as an electrician. I dealt with wires, breakers, and cranky customers. I built a good life with my wife, Marlene, in a modest house with a vegetable garden and wind chimes she insisted on hanging from the porch.

I used to laugh at the way they got tangled in storms. Now I miss that sound more than I care to admit. She passed away six years ago—lung cancer, even though she never smoked a day in her life. Just one of those cruel twists. I thought losing her would be the hardest thing I’d ever face.

But three years ago, our daughter Emily, 33 at the time, was hit by a drunk driver. She was walking back from the grocery store when a man ran a red light. Her body took the full hit—shattered spine, two broken legs, internal injuries. She survived. Somehow. But she hasn’t walked since.

Insurance covered what it could, but the kind of rehab she truly needed—specialized neurotherapy, robotic gait training, the whole package—was far beyond what I could afford. Most of my savings had gone to her surgeries.

What little was left, I used to move her in with me. I tucked a few dollars away for emergencies. Not enough to live on, but enough for a rainy day. She needed full-time care. I needed something to keep going.

I didn’t pick up a brush thinking it would save us. I picked it up because I didn’t know what else to do. One night, after Emily went to sleep, I sat at the kitchen table with a piece of printer paper and an old oil set we found in a box of Emily’s childhood things.

I sketched a barn I remembered from a trip to Iowa when she was seven. It wasn’t perfect, but I’d painted as a teenager. I just needed to shake off the rust.

I watched painting tutorials online. Oils, mostly. They felt heavy, grounded, real. I painted every night while Emily slept.

Slowly, I felt brave enough to take a few canvases to the park. I painted what I remembered—old country roads, school buses splashing through puddles, cornfields bathed in morning fog, rusty mailboxes leaning in the wind. Places that make you ache for something you don’t even know you’ve lost.

People stopped. They smiled. “That looks just like my granddad’s place,” one said. “That diner used to be down the street from me,” said another. Sometimes they bought a painting. Sometimes they just nodded and moved on. I said, “Thank you for stopping,” every time. That tiny connection kept me upright.

Last winter nearly broke me. Cold, harsh, bitter. My hands cramped so badly I had to shove them under my arms to keep blood flowing. I wore two pairs of gloves, but the paint still stiffened, and the brushes stuck.

Some days I made twenty dollars. Other days, nothing. I’d walk home with stiff knees and numb fingers, look at the bills piling up, then glance at Emily. Her face softened.

“Dad,” she said, “someone’s going to see what you’re doing. They’ll feel it.”

I pretended to believe her. She could always tell when I was faking. But she let me have it.

One of the worst parts of getting old isn’t the pain—it’s feeling like you’ve already given everything. Like the world is slowly forgetting you were ever sharp, strong, capable. That’s how I felt, watching my daughter sink and knowing I had nothing but a leaky bucket to bail water with.

And then one day, everything changed.

It was a cool early-fall afternoon. I was painting a scene I’d seen earlier that week—two kids tossing bread to ducks while a jogger ran past. I was halfway through when I heard a soft sound, like a whimper.

I looked up. A little girl, about five, stood by the paved path. She wore a pink jacket too big for her, hair in two lopsided braids, and clutched a stuffed bunny. Tears streaked her red cheeks.

“Hey there,” I said gently. “You alright, sweetheart?”

She nodded, then shook her head. “I can’t find my teacher.”

“Were you with a school group?”

She nodded again, sobbing harder.

“Come sit,” I said, patting the bench beside me. “We’ll figure it out.”

She shivered, so I wrapped my coat around her. She smelled like peanut butter and crayons. To distract her, I told her a story I used to tell Emily—about a brave princess who followed the colors of the sunset to find her way home.

By the end, she was giggling through her tears, still clutching the bunny.

I called the police. Fifteen minutes later, a man in a dark suit came running. “Lila!” he shouted.

She squealed, “Daddy!” and ran into his arms. He dropped to his knees, hugging her like he might never let go. Then he looked at me.

“You found her?” he asked.

“She found me,” I said, smiling.

“I… thank you,” he said, blinking fast. “Her teacher phoned me thirty minutes ago. I came rushing.”

“No need to thank me,” I said. “Just make sure she knows she’s loved.”

He crouched beside her. “Sweetheart, you scared me. What did I tell you about running away?”

“I wanted to see the ducks,” she said sheepishly.

He kissed her forehead, then turned to me. “Is there anything I can do to thank you?”

I shook my head. “No, sir. Just get her home safe.”

We talked a few minutes. I told him about Emily, why I paint. He nodded quietly, storing it away. Then he handed me a business card. “Jonathan. I run a company—Hale Industries. Call me if you ever need anything.”

I put it in my shirt pocket and watched them drive away.

The next morning, I heard a loud honk outside—not a car beep, a honk with rhythm. I peeked through the blinds. A pink limousine.

I blinked. “Emily, did you invite Cinderella over for brunch?”

A man in a dark suit stepped up with a briefcase.

“Mr. Miller?”

“That’s me.”

“You’re not painting in the park today,” he said, smiling. “Pack up your paintings. You’re coming with me.”

I’m 70. I’ve seen things. I’m suspicious. But something about this man made me trust him. So I loaded my cart and followed him.

Inside, sitting like a little queen, was Lila, bunny in her lap.

“Hi, Mr. Tom!” she said, beaming.

Jonathan looked polished, but softer now. “I wanted to thank you properly.”

I told him he didn’t have to. I didn’t want charity. He opened the briefcase and handed me an envelope. I opened it. Inside was a personal check. Enough to cover every cent of Emily’s rehab. Not just a few sessions—all of it. And even a bit left over for my savings.

“Sir… I can’t take this,” I stammered.

“Yes, you can,” he said. “And you will. This isn’t charity. It’s payment.”

“Payment for what?”

“For your paintings. I’m opening a community center downtown. I want your art on every wall. You’re doing something unbelievably special. Thousands should see it.”

I sat in stunned silence. “Places that feel like home,” he said, “that’s what your paintings are. That’s what people need.”

Lila leaned her head on my arm. “Daddy says you paint love.”

I nodded, tears rolling down my cheeks. We packed all the paintings. When I walked in with the check, Emily was at the window.

“What happened?” she asked.

I held it up. “A miracle, honey. A real one.”

Six months later, Emily finished therapy. Doctors said they’d never seen determination like hers. Despite setbacks, she stood. Then she took steps. Now she walks short distances with a walker. Every time I see her upright, I feel like I’ve been handed more time with my daughter.

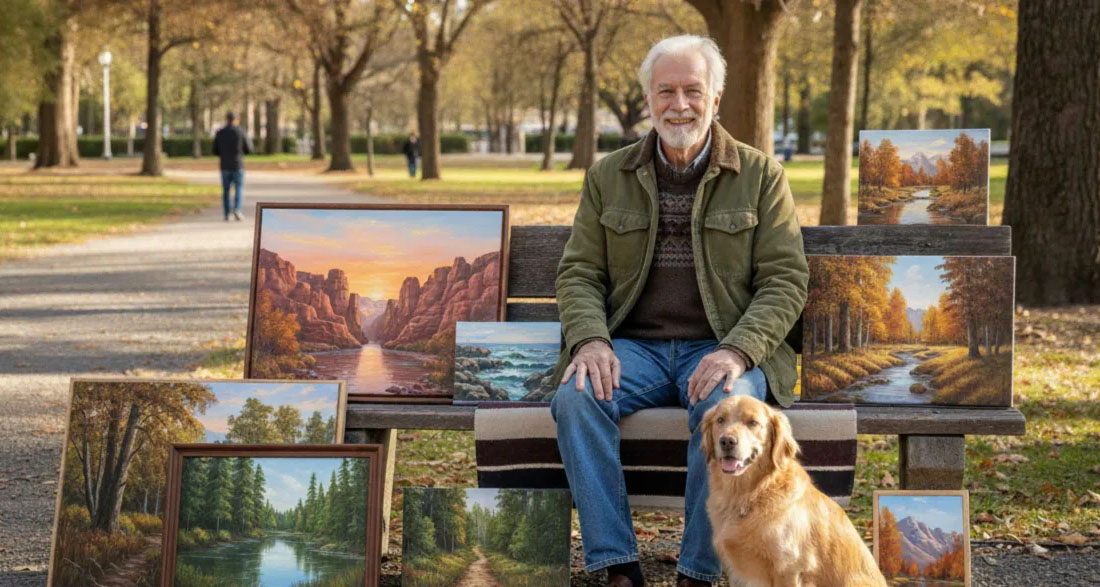

I still paint. Every day. Now I have a real studio, a salary, no more worrying about groceries. On weekends, I still set up at the same park bench—to remember where it all began.

When people stop and say, “That looks like home,” I smile. “Maybe it is.”

And I kept one painting for myself—a little girl in a pink jacket, holding a stuffed bunny by the pond. That day didn’t just change Emily’s life. It changed mine, too.